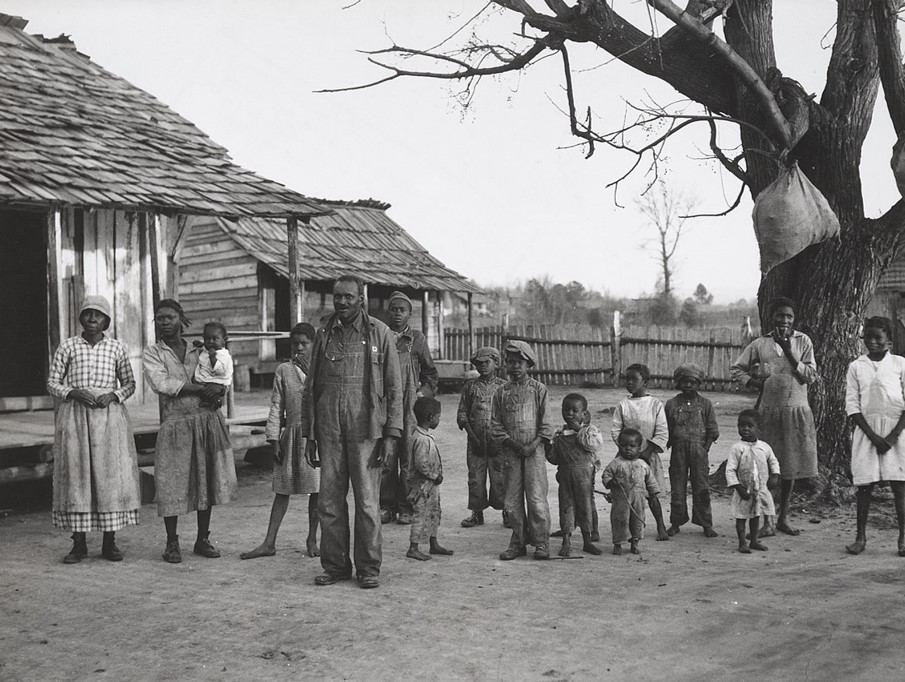

Arthur Rothstein [CC0]

CHAPTER 5

Confronting the Future

The seventh child of Wisdom harbors a heavy shame about her lack of education.

‘I loved-ed school,’ Mary Lee says, ‘but I loved-ed mens more.’

She left school in sixth grade, pregnant. She didn’t even know what pregnant was when she found herself on hands and knees

behind the cabin, throwing up the dewberries and dumplings she’d eaten for breakfast. Then she looked up and saw Aola’s troubled

face at the window.

School days are over for you, Aola said, explaining that a person was inside Mary Lee’s stomach.

Oooh!’ Mary Lee says. ‘That struck me! I cried all day long, telling the Lord to take it away. But the Lord wouldn’t move that. Some

things the Lord don’t move.’

A sixth-grader brimming with prayers and fears: How Mary Lee sounded is preserved on reel-to-reel tapes in the Library of Congress . After the Roosevelt program was launched, government workers recorded hours and hours of everyday life at Gee’s Bend, including sixth-graders singing a hymn to which Mary Lee still knows every word by heart:

"It may be trouble at the ferry,

I’m gonna stand there anyhow.

Dear Lord! Dear Lord! Dear Lord!"

Because she was 14 when she became a mother, childhood and motherhood are all jumbled up in Mary Lee’s mind.

She’s reliving both this morning, driving around the river to attend an important assembly at her grandsons’ high school.

Mary Lee’s three grandsons--17, 16 and 12--stay with her because their parents live in Mobile and can’t handle them. There were

nasty scenes, she says, loud arguments, and she had no choice but to take in the boys. ‘It’s a terrible thing to be afraid of your own

child,’ she says vaguely.

Mary Lee has spent her life among swarms of children. She had 16 siblings growing up. She had eight children of her own, who have

given her 30 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren so far. There should have been more. She once saw herself having 15

children. Then came a hysterectomy, and seven of her unborn children were stranded, no way to cross over into this world.

With them is her baby, who died in his sleep. Mary Lee never knew why. ‘Pretty baby,’ she says. ‘Smiling all the time.’

She can see him. He always was a late sleeper, and one morning she let him sleep awhile longer. When she finished her chores and

got the other children off to school, she went to wake him. ‘He had a real pretty smile on his face. And I said, ‘Boy, you better wake

up!’ Then I said, ‘Boy, you better straighten out. What you so stiff for?’ Then I busted out crying.’

That boy, he’d have grown up to be sweet-tempered like his mama. Not like her grandsons, she says with a snort. Since she’s been

sick, unable to crawl out of bed some days, the boys have been running wild, giving her sass. Mostly, they just ignore Mary Lee.

They clod sulkily through her house, speaking only to ask for pocket money. Even when she saved enough from her $382 monthly

Social Security checks to buy them a computer, their mood didn’t improve.

Photo by Nathan Anderson on Unsplash

"For the first time in 35 years, the children of Gee’s Bend wouldn’t be slaves to the bus.""

If they seem angry, sometimes they have cause: They spend half their day on a slow-moving bus. The 12-year-old goes to school at

the top of the U, but the older two attend high school in Camden, and circumnavigating the river consumes their youth.

The children, Curl and Hilliard are quick to note, would benefit most from a new ferry. Ten minutes to Camden, 10 minutes back.

For the first time in 35 years, the children of Gee’s Bend wouldn’t be slaves to the bus. They would be able to take part in afterschool

plays, sports and teacher-student tutorials. To those on both sides of the river who fear the change a ferry would bring, Curl and Hilliard insist: A ferry wouldn’t be for you. It would be for the children, heirs to the civil rights movement’s bravest warriors, and such special children deserve a change.

Mary Lee doesn’t disagree. She’d just rather see Curl and Hilliard build the children a new school in Gee’s Bend. Or a community

center. Or a store. Something to keep the children here, and Gee’s Bend alive.

Now, after the long drive around the river, Mary Lee settles into a chair in the high school auditorium, fidgeting, nervous to be in a

school again. One of the first speakers puts her at ease. ‘Where I’m from,’ he says, ‘we take away the big words, like ‘statement of

purpose.’ Instead, we say, ‘How come us here?’

Mary Lee giggles.

Parents are here, he says, to learn about stiffer state requirements for a high school diploma. Students are here because their parents made a mighty sacrifice.

You here,’ he tells the students, ‘because somebody sweated for you! Somebody dragged a long sack of cotton through the dirt!’

‘Mm hmm,’ Mary Lee moans, as though in church.

For an hour, speaker after speaker explains the new diploma requirements, with pie charts and graphs. Mary Lee doesn’t understand much of what they say, until one speaker waxes about the value of education, wounding her deeply in the process.

‘If you don’t graduate from high school,’ he bellows, ‘you spit in the face of Martin Luther King!’